Creating Morally Emotional Messaging

Dove’s “Real Beauty” remains one of the most memorable ad campaigns and quite fittingly, it’s aged gracefully. Even though it was launched in 2004 (think Bush and Blair, the Motorola RAZR, and Mean Girls), it’s still being brought up as an example of great emotional advertising.

We all want our messaging to hit the high notes like Real Beauty did, but as the slew of shallow, saccharine marketing content suggests, creating effectively affective messages is more difficult than simply telling your team, agency, or production house that you want something powerful and emotional.

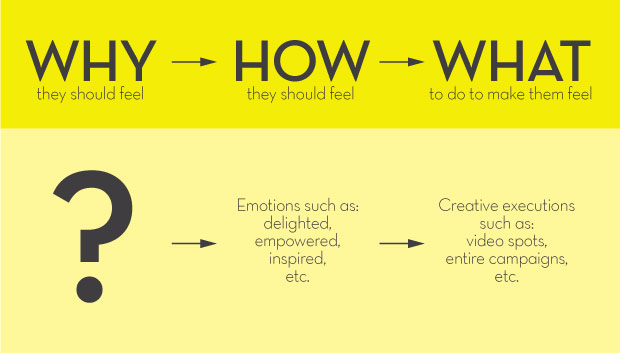

Other than considering how we want our audience to feel, we also need to think about why they should feel that way. Failing to understand that crucial why while trying to create affective content will likely result in blandness, superficiality, and most importantly, a failure to connect with your audience in any meaningful way.

I had the opportunity to work on a campaign centered on “happiness” in my junior advertising years. It kind of made sense from the client’s perspective—they’re an ice cream brand and ice cream makes people happy. But beyond that, there wasn’t any mention of why people should be happy. The resulting campaign, although well crafted, was severely restricted by the superficiality of the theme.

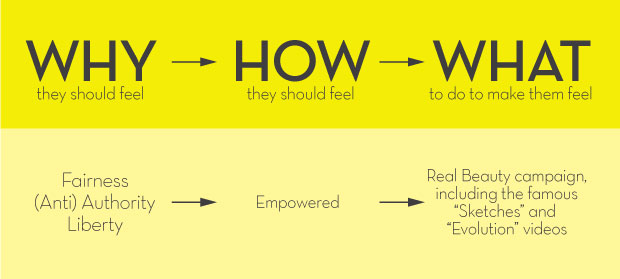

In terms of messaging effectiveness, the major difference between the Real Beauty and Happiness campaigns is that the former managed to evoke some very important and primordial moral issues within its audience—fairness, subversion, and liberty.

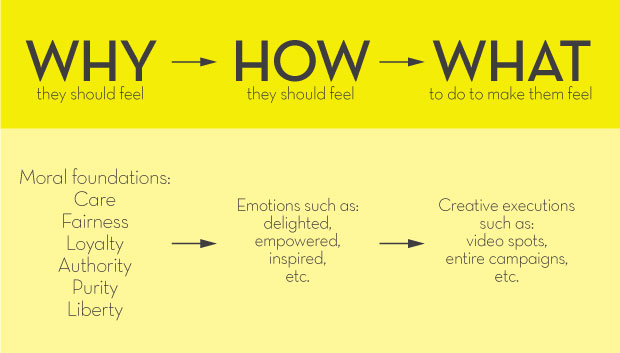

These are three of the six moral issues Professor Jonathan Haidt identified in his Moral Foundations Theory. Our species, from our ancestors all the way down to our generation, cares about these moral issues because doing so helps us survive and thrive in social environments. Essentially, these six moral issues are hot button topics which are likely to elicit strong emotional responses. If you look at successful brands, cults, or movements, you’ll find manifestations of some (or all) of these moral triggers at the core of their existence.

The Moral Foundations Theory has been used to explain the intense political polarisation in the United States. And if the theory can provide powerful insights into issues such as why people vote against their best interests, how political parties in one of the world’s most competitive and high-stakes democracies craft their messaging, and how politics divide Americans into fervent tribes, you can certainly use it to create effectively affective marketing.

As a short case study of how we can apply the Moral Foundations Theory in marketing, here’s how Dove’s Real Beauty campaign appealed to its three moral themes:

- Fairness—Every woman is beautiful, not just the ones who were born with certain features that have been deemed attractive by society.

- Subversion/anti-authority—We’ll not allow the fashion or cosmetic industries, or the patriarchy, to dictate what beauty is.

- Liberty—We want women to be free from society’s definition of beauty.

Real Beauty didn’t merely tell women to feel empowered, it told them that they deserve to called beautiful as much as a billboard model does, that they deserve to be free from the narrow definition of beauty, and screw “The System” that insists on propping up that narrow definition. With this messaging angle defined, Dove’s agencies were able to come up with brilliant content such as the “Sketches” and “Evolution” videos.

In some situations, the application of the Moral Foundations Theory may not be so straightforward. Here are some nuances to take note of:

Nuance #1: Know your brand and audience first

The Toyota Prius and the BMW 7 Series are in the same broad category of automobiles, but they’ve been sufficiently differentiated to attract different segments. Hence, both brands appeal to different morals—the Prius appeals primarily to Care (for environment), and with hints of Fairness (“Let’s protect the environment for future generations”), and Purity (by reducing contamination of the planet).

On the other hand, the BMW 7 Series is more likely to appeal to Fairness (not in the sense of equality, but “Those who achieve more, deserve more”) and Authority (a.k.a. BMW owners are likely to be near the top of socioeconomic hierarchies).

However, if your brand and audience aren’t as well defined, work on that first (the Moral Foundations Theory can also be applied there) before trying to craft an emotional message. Congruence before conception.

Nuance #2: Is your audience WEIRD?

WEIRD = Western(ised), Educated, Industralised, Rich, and Democratic. If your audience ticks all these boxes, they’re likely to be more individualistic and see the world as separate objects. Hence, some moral appeals may not be as effective. The example below is from the Norwegian Army.

Norway (and its Scandinavian neighbours) is about as WEIRD as you can get, so it’s no surprise that its army has decided to go with a more individualistic appeal to Liberty (“We exist so that you can continue living your way”) instead of a more direct and traditional appeal to Loyalty (e.g. a nationalist message like “For King, country, and the flag’s honour”). The result: effectively affective advertising.

Nuance #3: If done right, you’ll create opposition

As Maurice Saatchi said, “If you stand for something, you will have people for you and people against you.”

The Dove Real Beauty campaign attracted naysayers who derided the notion of redefining beauty. Prius drivers have no shortage of haters calling them out for virtue signalling. BMW drivers aren’t exactly perceived as pleasant people to share a road or parking lot with. For every action, expect an opposite reaction.

If you can’t bear the thought of creating opposition, consider the second half of Maurice Saatchi’s quote, “But if you stand for nothing, you will have nobody for you and nobody against you.”

And that really is the essence of why you should start thinking about your brand through the Moral Foundations framework—getting people on your side. Not all messaging needs to evoke grand moral themes and high emotions (I remember seeing a telco brand advertising slightly lower prices with socialist revolution motifs), but if you’re going for an emotional reaction, just be sure to ask, “Why should they feel what I want them to feel?”.

Thumbnail image was sourced from CBC.