Selling Excuses: Helping Consumers Disguise Signals of Status and Sexual Attractiveness

Free-flowing alcohol, flashing lights, smiles all round. It’s easy to mistake the nightlife scene as nothing more than just fun.

However, the sociologist Ashley Mears’ study of VIP clubs reveals how much deliberate planning goes into creating this image of spontaneous celebration, which masks the elite nightlife industry’s real purpose: To allow patrons to show off without looking like they’re showing off.

Mears embedded herself as one of the “girls”, an industry term for the tall, young, and beautiful women who lend their prestige to clubs and their high rolling patrons in exchange for a few drinks and sometimes a meal or two.

The sheer number of high-status girls like Mears who seem to be doing nothing but merely hanging out in a club elevates the venue and its patrons. (Not unlike the role of expensive furniture.) This relationship can only be feasible if the girls are compensated in drinks instead of actual money, as it maintains the illusion that they’re not working.

Bottle service at such venues were not designed with subtlety in mind—oversized bottles of champagne with glow-in-the-dark labels or diamond adornments, escorted by scantily-clad women holding sparklers. And just for good measure, the DJ may also interrupt his set to announce the big order. After the bottles have arrived, the VIP patrons may not even drink from them but choose to share or spray the champagne instead.

When it’s time to pay, the staff shines a brighter-than-necessary flashlight onto the head of patron footing the bill.

As you can see, there’s a lot of conspicuous consumption going on but always with sufficient plausible deniability for the club patrons to disguise their signals of wealth and status. The girls? Just chilling. The over-the-top bottle service and spraying of champagne? All in the name of good harmless fun. Spotlight on the person casually paying tens of thousands of dollars for a night out? Helps him see in the dark.

But why disguise those signals? Simply put, nobody likes a show-off. In most societies throughout most of history, overt “big-shot” behaviour is often the target of gossip, or worse. The general aversion towards excessive dominance has been enshrined in concepts such as “the tall poppy syndrome” (Australia and New Zealand), “Janteloven” (Scandinavia), and “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down” (Japan).

It’s not just shame from others that makes people cautious about showing off, guilt from within oneself also plays a role. In fact, guilt is a recurring theme in studies of modern affluent consumers, possibly exacerbated by factors such as the spread of egalitarian ideals and dramatic increases in wealth inequality.

One of these studies features a memorable observation about rich New Yorkers scribbling out the prices of new purchases to prevent their domestic helpers from seeing them. The helpers, of course, know how rich their employers are. Such a behaviour can only be explained as a way for the affluent to sidestep their own guilt.

Yet, people still have to signal their status. Even if not to move up the ladder, then to merely avoid slipping down the hierarchy. Indeed, signalling is a major component of doing business, settling in a new neighbourhood, or any form of social interaction; to show that you belong, if nothing else.

Signalling may be even more important in W.E.I.R.D (Western(ised), Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) societies as there are more opportunities and incentive to seek out new friends, working partners, etc. In such situations where people have little to no information about each other, signalling to give others a good first impression seems like a very sound idea.

Just like in the nightlife industry, luxury brands have also taken into account a similar dilemma faced by their well-heeled target segments who want to signal with luxury goods but also need to be able to justify the purchase to themselves and others. It needs to be more than pure hedonism.

My favourite example is from the luxury watch market, which often features timepieces with depth gauges. I don’t know much about diving, but I simply can’t imagine a significant cross segment with luxury watch wearers. The presence of a depth gauge may help the wearer signal some sort of proclivity towards the outdoors and adventure, but it also certainly fits the definition of a “functional alibi”.

The term “functional alibi” is roughly equivalent to what I meant by excuses or plausible deniability. It was invented by a team of academics who investigated precisely the phenomena of luxury goods with somewhat trivial utilitarian features that ultimately serve to help customers justify the purchase.

Their research results heavily support the important role of such functional alibis in luxury products.

- Consumers were more likely to mention utilitarian features (e.g., “easy to clean”) when reviewing purchases of luxury products than when reviewing less expensive products

- Consumers less likely to mention utilitarian features if the luxury product was purchased as a gift (i.e. they felt less guilt and hence, less need to justify the purchase if it’s a gift; also, hedonism is much more acceptable, or even desired, in gifting)

- Consumers were willing to pay about 50% more for a luxury bag with an added utilitarian feature (small attachable pouch)

- In the case of a luxury watch purchase, consumers valued an included utilitarian feature (emergency phone charger) 5 times more than if that feature was to be bought separately

- Potential buyers were more likely to purchase a luxury bag if a utilitarian feature (attachable pouch) was included; the most likely explanation is that the pouch offset some of their guilt since it has no effect on consumers who weren’t able to afford the bag in the first place

- Potential buyers thought they’d use the utilitarian feature (pouch) much more than consumers who weren’t able to afford the bag

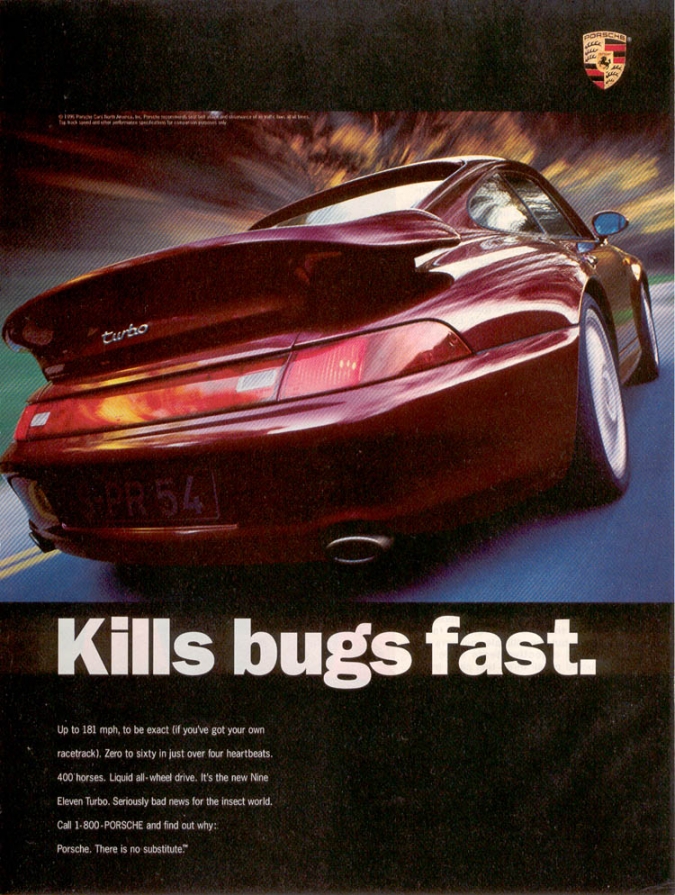

People who hold a more traditional notion of luxury, which deems some items luxurious because they don’t provide any tangible utility other than conferring status by being unobtainable for most, will probably find the notion of functional alibis quite strange. Porsche poked fun at the absurdity of the situation with this ad in the mid-90s.

Put another way, the presence of functional alibis/plausible deniability/excuses helps to manage the tension between consumers’ innate (and hidden) motivations and what their own moral selves and others deem to be acceptable. This tension is also clear when it comes to women’s desire to signal their sexual attractiveness.

Society and even science used to view women as passive actors when it comes to attracting partners. But just watching the great sociological analysis titled Mean Girls (2004) will confirm what more recent and nuanced developments in science have revealed: Women are very much active participants in the mating game, but it’s in their best interests to compete without looking like they’re competing.

An example of helping women do just that comes from the activewear industry. Just decades ago or even now in many parts of the world, a woman dressed in nothing more than a pair of sports bra and leggings would’ve attracted scorn from other women (as well as overly eager attention from men). It’s more acceptable now certainly thanks to societal shifts but also to the activewear industry framing such fashion as part of a modern, hard-working lifestyle or within a grand idea like empowerment.

Disguising sexual attractiveness signals isn’t limited to women; men want to look good and deny trying to look good too. Overtly masculine barbershops and grooming products to the rescue. Men can now enjoy all the preening and pampering without thinking of themselves as or being accused of metrosexuality or femininity.

With highly visible accessories such as wristbands and pins, savvy nonprofits have also benefited from letting their donors signal their altruism while helping them maintain some level of deniability. Any suggestion of virtue signalling can be waved away with the unassailable need to raise awareness for such charity causes.

Do you have any other examples of companies and organisations providing consumers with plausibly deniable ways to signal something about themselves? Send them over as I’m always happy to add more to my notes.