The Funniest Church Gathering Ever

A thin-faced man on the stage confessed, “I thought I would spare you the analysis and tell you upfront that I’m a sinner.” The audience erupted into laughter.

“I am a man who is prone to freeze up when he is tired and feels instinctively justified in blaming it on somebody else.” Again, the congregation howled in amusement.

As a religious teacher who regularly speaks about the very serious topic of mental health, John Piper is the furthest thing possible from a stand-up comedian. But suddenly, he found himself drawing the kind of laughter many comedians can only hope for.

Unable to bear how odd the situation was, Piper went off-script and remarked, “You’re a very strange audience.” Of course, more laughter.

Don’t worry if you don’t find his speech hilarious. Piper didn’t either. He was baring his soul to emphasise the importance of mental health among the Christian community, and the large crowd of Christian counsellors was reacting like it’s the funniest thing they’ve heard all day.

What was going on?

Turns out, John Piper was moved up the event schedule but nobody informed the audience. The other speaker he replaced was a comedian.

This little mix-up is a great example of how powerful framing can be. Thinking John Piper was the comedian who was supposed to perform in that timeslot, the audience was ready to interpret everything he said as a joke.

(If you’re curious, you may watch Piper’s speech here.)

Framing isn’t exactly a groundbreaking topic

We all know what framing can do—Apple repositioned itself as a lifestyle brand to capture the mainstream market, the “Got Milk?” campaign resulted from a reframing of “Milk is good for you” to “What would you do without milk?”, and bars have found a clever way to charge higher prices during peak hours without any customer complaints by reframing their non-peak hours as “happy hour”.

What is groundbreaking, though, is how far our understanding of the human mind has come, and how this knowledge can be used in effective framing that results in real behaviour change.

Growth vs. fixed mindsets in learning

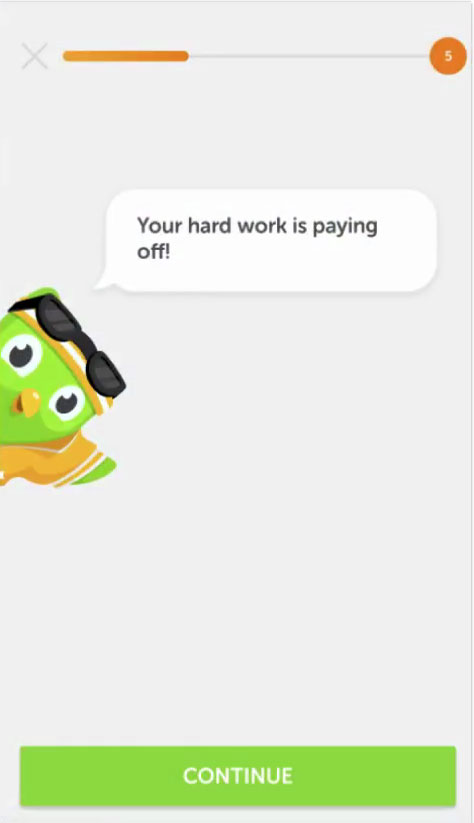

Duolingo is a mobile app that helps its users learn new languages. Of course, learning a new language takes time, so Duolingo was looking for ways to help users stay on the app. They applied the psychology of growth mindsets to the app copy, emphasising on the users’ effort with encouraging messages such as “Your hard work is paying off!” Compared to more neutral copy like “You’re doing great!”, the new growth mindset copy alone resulted in more daily active users, more completed lessons, and more user retention.

Appealing to people’s morals for a greener environment

Getting people to be more concerned about our planet’s health can be a surprisingly tough sell. The effects are long-term, distant, and not always visible. And for reasons previously unknown, people who lean towards being socially conservative tend to be less conscious about the environment. To pro-environment folks, this can be frustrating because it just makes sense to care about the environment. Hence. most pro-environment messages focus on care—care for the environment, love the planet, etc.

Then, moral psychology came along and found that socially conservative people experience morality differently. Care isn’t the only moral value that’s important to them. Pro-environment messages that focus on care don’t quite resonate with them. To borrow an analogy from Jonathan Haidt, a leading scholar in moral psychology, promoting pro-environment attitudes with only care is like opening a restaurant that sells only sour food; you’ll attract some customers who love lemonade, but you’re missing out on many people who like other flavours.

Another major discovery in moral psychology is that morality is automatic. We don’t have much choice in the things that offend or please our moral intuitions. This means moral emotions can be powerful enough to greatly influence our attitudes and behaviours.

Combining these two insights, researchers have managed to encourage more socially conservative members of their study to develop pro-environmental attitudes. They achieved this by reframing pro-environment messages in terms of purity instead of care, The reframed messages resonated much more with a previously indifferent crowd after they’ve been flavoured differently.

(I’ve also written about the application of moral psychology to marketing here.)

For better and worse

Framing is a tool that can be used for great purposes like the ones listed above, but it can also be used by politicians.

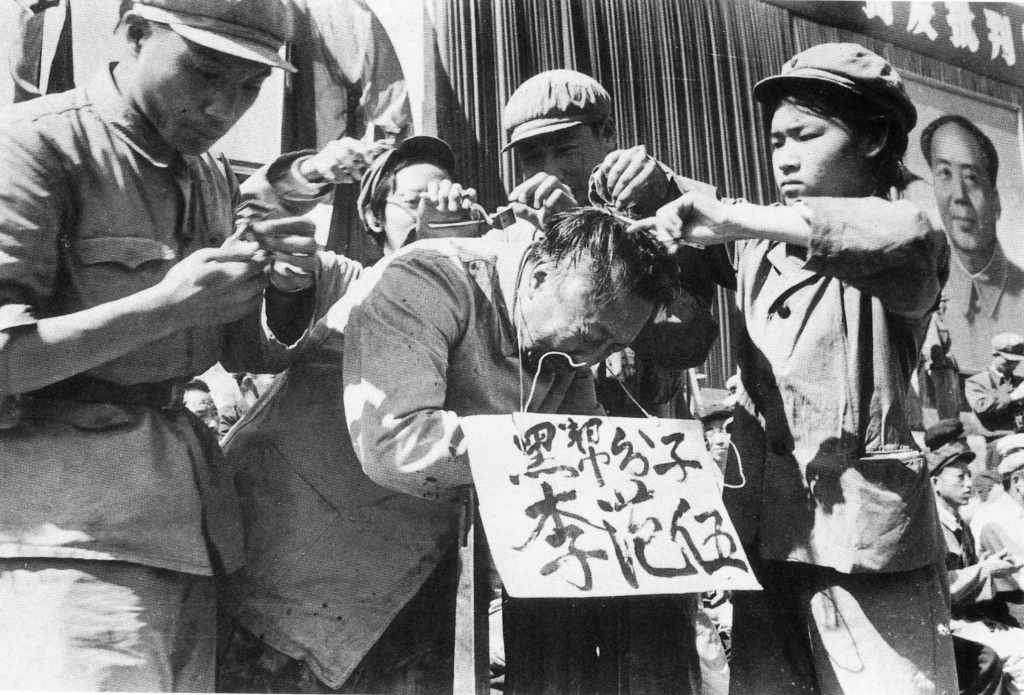

From Nazi Germany to The Red Revolution in China to the Rwandan genocide, politicians have found scapegoats to blame all their societal problems on. And they have framed those scapegoats in a particular way that has managed to arouse the people’s attention—by appealing to the people’s innate sense of disgust. The Nazis have framed the Jews, homosexuals, and gypsies as parasites and diseases. The Red Guard referred to “class enemies” as dogs. The Hutus mercilessly murdered their Tutsi neighbours after they were rebranded as “Tutsi cockroaches”.

This frame works so well in directing mass anger towards a group of scapegoats because our sense of who is Us and who is Them is fuelled by the fear of contamination. This frame speaks straight to people’s primal instincts, “They are not part of us and they have to be avoided.” Furthermore, reframing Them as parasites/dogs/insects removes their humanity. It’s not moral to kill humans, but it’s okay to kill non-humans. As history have shown, this kind of framing has been devastingly effective.

Well, that’s been an emotional rollercoaster; we began with a lighthearted story and ended with some gruesome ones. The main takeaway is this: framing is powerful, but only when we have an in-depth understanding of human psychology. There are no checklists or best practices for effective framing, as it’s partly a creative process. But it helps to be endlessly curious about people. With all the technology in marketing, it’s easy to forget that our industry is still essentially about people and their psychology. Stay curious; that’s the reason why we fell in love with marketing in the first place.